My biggest weapon by far is the ability to work out a good sequence. I made countless changes to it over two days in early October, ending up using some holds with the opposite hand to Neil and Steve, as well as a couple of holds they don’t use at all. One of these allowed me to shake my left arm before taking the crucial crimp in the groove where Steve fell. With this sequence, I linked the climb completely on the shunt six times across two sessions and knew the route was possible. A summer of various mishaps in 2021 had left me a bad case of tennis elbow and this was really limiting me. I couldn’t try the route for long before it hurt too much, and I was not in anywhere near good enough shape to lead it. October was pretty wet anyway and most of the time I’d tried it there were wet holds.

I was working on the assumption I’d just get it all as sussed as possible before winter and then come back the following spring. Task number one was to recover from the tennis elbow to even begin training again. The elbow recovered steadily and I could tentatively start on my 45 board in early November. Even just a few sessions on the board gave me some confidence and in late November I optimistically went down with Iain Small to lead Lexicon. Sadly, the overnight rain had been heavier than expected and it was seepy. At least it drew a definite line under proceedings for the autumn and I could move on.

I planned my winter training as such; December - board. January - boulder projects outside, February and March - endurance training on the board. Training plans rarely survive real life intact, but this one seemed to roughly hold up and as March progressed I had many boulders between 8A and 8B+ under my belt, plus a reasonable amount of endurance work, for me at least. There were niggles; a tweaked finger joint and my usual ankle issues that suddenly seemed to flare. Could I even walk in?!

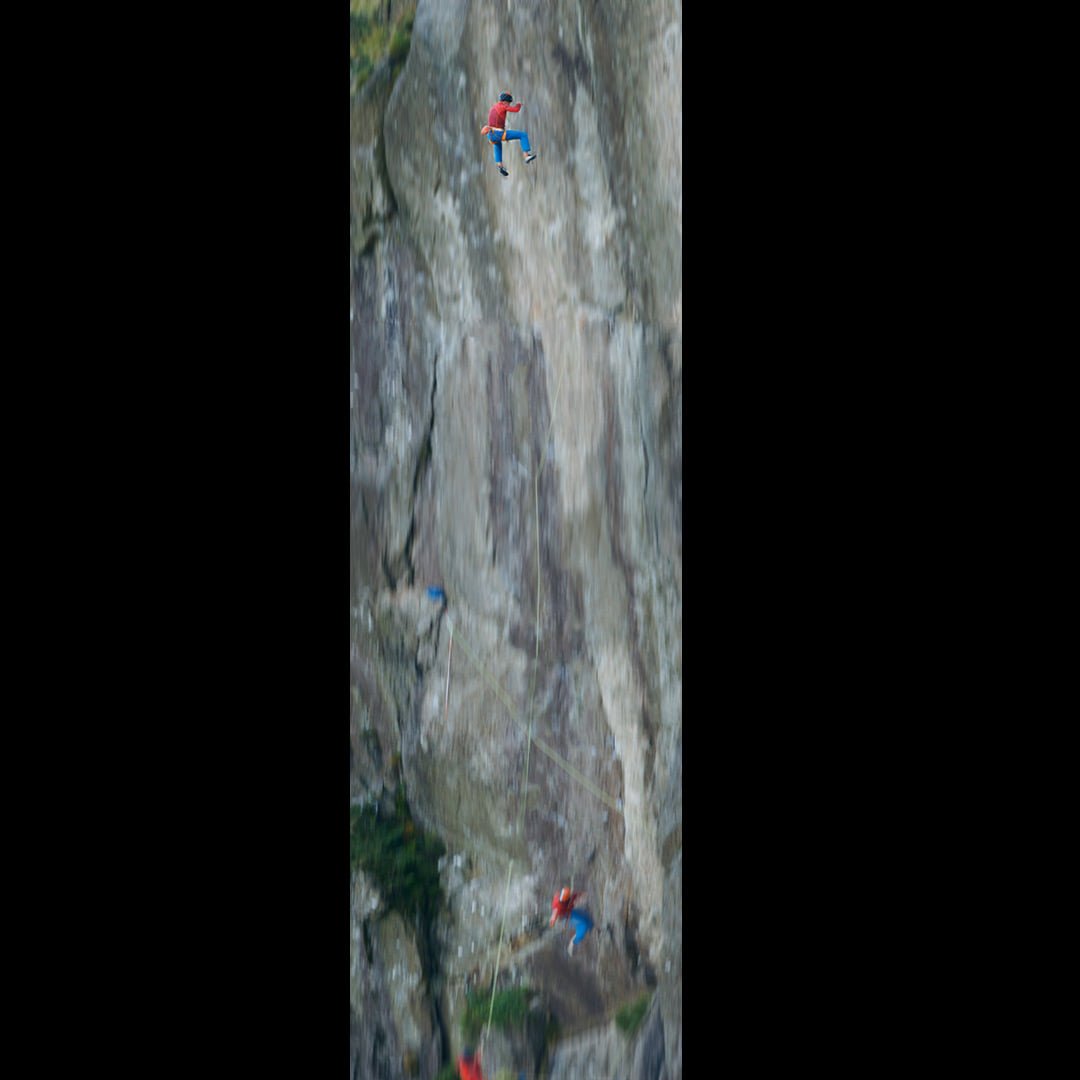

On the stellar late March forecast I went to find out. I was indeed a bit hobbly but could get to the crag. It was lovely and dry but the wind was raging and I could not warm up. Yet I could link it with my big belay jacket on and numb, glassy fingers. A good sign. I just needed that one confirmatory session in more reasonable conditions. After a rest day, I got it and linked the moves repeatedly, placing all the gear and trailing a lead rope, sussing out exactly how to extend all the runners. Game on. Chris messaged, keen to take pictures if I was trying it. I said it was ready to go and so Natalie and Chris joined me in Ambleside a couple of days later.

On our day on the hill, that keen March wind had died completely and I now was back to the opposite problem of ‘too warm’. Your fingers have to bite those rhyolite crystals. If it is too warm, my skin just rolls off them. This did not fit within my ‘thorough protocol’. How would I feel if I greased off the last move and dropped the length of the crag, for the sake of waiting for a breezy day? And yet, the fact I’ve arranged a climbing partner does weigh on me. I felt bad enough dragging Iain up there and felt silly as we sat about in 4 degrees looking at a dripping crag. If I could just get a half hour of wind, I could see it off. I also had a hunch that I was in good enough shape to just scrap my way up it even in less than perfect conditions. Why not just finish it?

Unfinished climbs have always been a source of chronic pain to me, an ache I can tolerate for long periods when there is no other option. But the minute I can change the picture, I’ll do anything I can to resolve it. When I say ache, I mean that in a good way, like the ache of burning muscles in training. It’s good pain! The minute I resolve it, I’m almost instantly looking to cause it again and have lived this way for 25 years. There is an expression that pain is the cost of being alive and as far as I’m concerned, it’ll stop when I’m dead.

Little bits of breeze came and went and so I continued with preparations. Final bits of velcro were attached to screamers, the rack was laid out on the grass and then attached to my harness in order and we abseiled down. At the absolute minimum, I wanted to force myself to climb to the nut and skyhook on the headwall, no matter the conditions. I could have the opportunity for a confidence building fall from the sloper where Neil did his super high step. If I got to the skyhook and nut, I could test exactly how efficiently I could get them in on the lead. It’s always more of a faff than you would like. If the breeze suddenly picked up and I could hang that wee side pull long enough to get the hook in, maybe I could just commit? Delaying this decision right to the last moment is a classic psychological tactic. It nearly always works, as long as you have the experience to be able to deal with hitting the ‘go’ button when the moment comes.