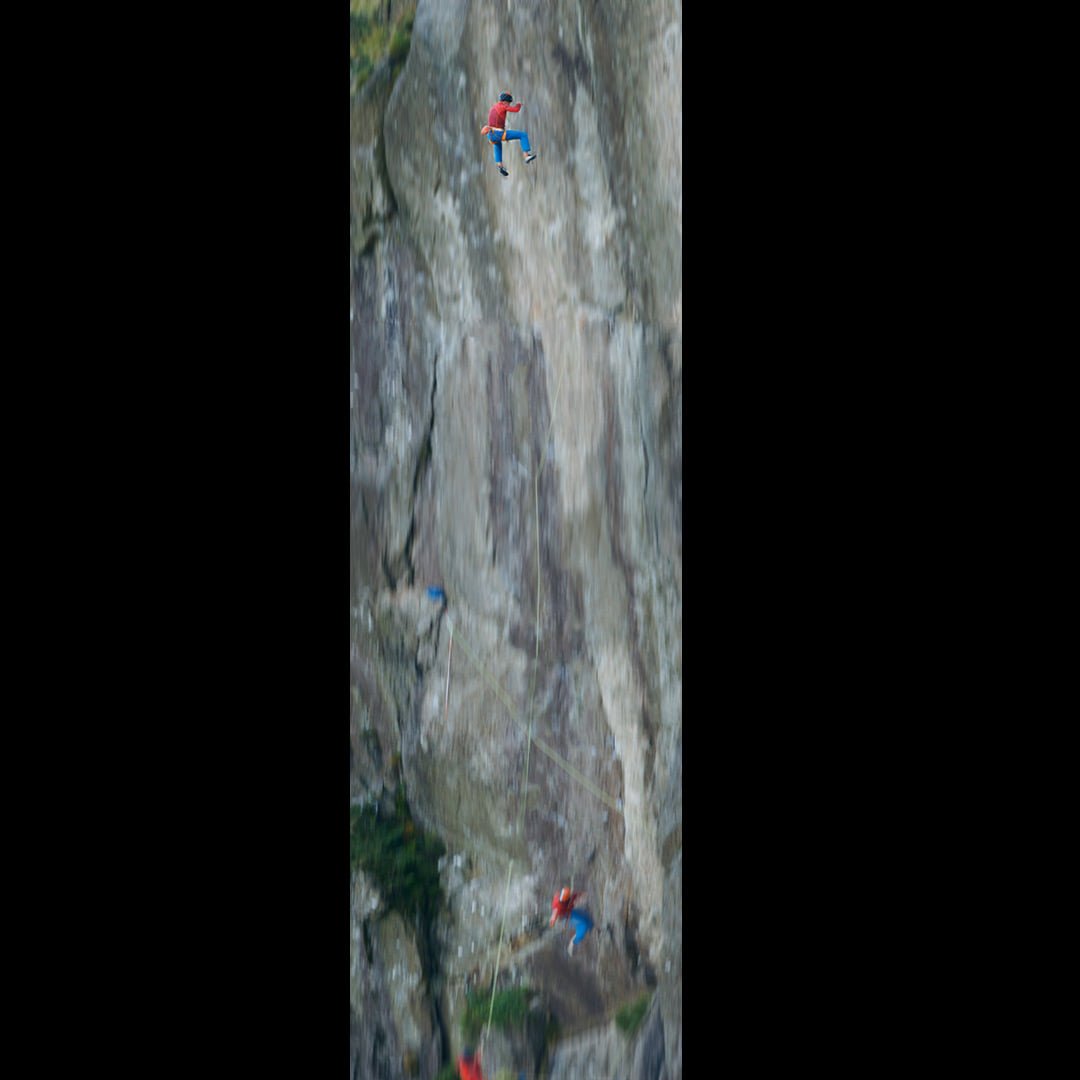

Lexicon, 3rd ascent

Setting up for the crux of Lexicon, a lunge out right to a slot. Photo: Chris Prescott

My first route in the Lake District was Breathless, John Dunne’s E10 7a on Gable in 2005. I’ve always been absolutely fascinated by hard trad routes and before I could try them, I built up a huge debt of curiosity about the hard routes I’d read about, that I’d need to pay back at some point. I wanted to know what the holds were like, to understand what level of physical and mental prowess you’d need to dare to start up them. I remember seeing a picture of Lakes climbing legend Dave Birkett in a climbing magazine, looking very much the honed athlete. For me, that combination of athletic ability and competence to put it to use on serious mountain trad was inspiring. I can’t remember why I chose to go at Breathless first. Maybe it was just the nice picture of John Dunne on the first ascent. Maybe Birkett’s testpiece If Six Was Nine E9 6c sounded way too dangerous.

I was otherwise occupied in 2006 but came back to the Lakes with Claire in 2007 and went straight for If Six Was Nine. It was a spicy lead and I was glad to have a decent amount of experience behind me before I went near it. I had only just turned onto the M6 to drive back north and my phone went. It was Dave Birkett ringing just to say well done, a gesture I appreciated a lot. Around the same time, I had a nice weekend with Kev and Steve and repeated another gnarly E8 of Dave’s, Caution on Gillercombe buttress. A benchmark at that grade and again not one to do for your first E8. The following day I persuaded the guys to go up to Pavey Ark to try Impact Day. It was originally given E9 6c but settled out at E8. The rock on that wall was beautiful and I just could not resist leading it that day.

Repeating Impact Day E8 6c on Pavey Ark in 2007. Photo: Steven Gordon

Since then I’ve only visited the Lakes a few times, once in 2016 to do Return of the King E8 6c up on Scafell, also a route with lovely rock. Last September I glanced at my feed and saw that Neil Gresham had climbed a new E11 on Pavey Ark. I stopped what I was doing and read the whole article about Neil’s new route Lexicon instantly. There was no point kidding myself on, I might as well decide right now that I would be travelling to the Lakes next week.

There are some things in life that you know you’re just going to have to go and do. Might as well get on and do them. I recalled the lovely rock on the wall and so the prospect of a route here with such a massive grade would surely present a brilliant climbing challenge. Aside from that, I was also highly impressed with Neil’s effort to climb the route. I interviewed Neil on my Youtube channel a while ago and in that piece, I asked him about his continued significant improvement in climbing throughout his 40s and into his 50s. I’ve spent many years studying physiology and so of course I know that this is possible. But possible and actually doing it are two very different things. Almost no-one does it because discarding habits, forcing new ones, breaking glass ceilings of your own making and essentially reinventing yourself is not easy. You need to be driven by something to make this happen. I suspected that perhaps the quality of the climbing on this wall might have been a significant driver for Neil. If it was as good as it sounded, I too could let myself become locked in to the one-way journey of obsession, starting with the M6 south.

Repeating Return of the King E8 6c on Scafell in 2016. Photo: Steve Ashworth

A week after Neil made the big lead of Lexicon, E11 7a, I pulled up in the ever packed car park in Langdale and slogged up to the top of the crag. I flung my rope over the edge and sat down for a cup of tea in the sunshine when I noticed two guys on the shoulder across from the crag, soon recognising their two distinctive accents carried across the gully on the breeze. Neil Gresham and Steve McClure. They were up with Alastair Lee, finishing off a bit of filming on Lexicon and Steve was keen to try the route. It was great to sit and chat with them about the climb and life in general.

We got on the route and I did do all the moves straight away. It was an okay start but doesn’t mean all that much on a steep sustained route like this. At first I used a similar sequence to Steve. But a terrible pinch hold he seemed to use without a bother felt like the living end to me. Steve is just so strong on tiny fingery holds like this, it’s incredible to watch, desperate to emulate. Neil explained his sequence. For starters, I couldn’t do the first crux as Neil had done, with a foot still on the girdle break. Neil’s high step move from this position is an awesome thing to behold. No wonder he did ballet lessons for it. Thankfully there were other footholds and I could do in four foot moves what he did in one. As I sat at the top talking to Neil, Steve appeared over the top with a look of ‘Oh shit I’m going to have to lead it’ written all over his face. Sure enough, he announced that he’d linked the moves. Although he said nothing about leading, it was quite obvious that was what would be happening.

It was far too hot for a Scotsman and I had no skin left to try again, so headed down to the shoulder and sat with Alastair as we watched Steve go for his ‘look’. He ‘looked’ his way smoothly up most of the massive runout up the headwall. As he locked off and took the crimp in the little groove before the redpoint crux at the last few moves, it was crunch time. I don’t get to watch many other people do this. It’s normally me feeling the fear as the commitment suddenly hits you. I couldn’t help but relate to what he must be feeling. Being Steve, he looked controlled, although I detected just a note of tension in his movement. It’s reassuring to know that perhaps he feels it too, when way out on a limb. Just then, his foot popped off during a balancy move, pulling in on a tiny nubbin for the right foot. If it had been a split second later, it might not have mattered, but he didn’t quite have his right hand in a shallow pocket. His body wobbled for a fraction of a second and then he just dropped. He shot essentially the full height of the crag, coming to rest with a stiff bounce about three metres off the deck. Silence. Both Neil and Steve sounded a bit shocked. No shit.

Steve McClure’s monster fall from before the crux. Montage: Alastair Lee

After they absorbed the events and set about de-rigging in the gathering dusk, I jogged off down the path and drove back to Roy Bridge, also absorbing the events. That day I had learned that I am no ballet dancer, I cannot move statically off ‘nothing’ pinches like Steve McClure and I did not like the look of that fall. Yet I still wanted to do the route. Steve returned a few days later and finished the job, as one would expect. He commented that he had to replace his usual psychological tactic of pretending he was just going up for a top rope try and then ‘sneaking up’ on the decision to lead before the prospect became scary. This time he knew he would be leading and he wondered how folk like myself deal with this. I have only one strategy to throw at this challenge; thorough preparation.

I resolved to return to Lexicon with thorough preparation in mind, taking my time and aiming at an incident free ascent with no falls. Slips notwithstanding, the most likely place to fall off the route would be the very last hard move, higher than where Steve fell. That would be uncomfortably close to the ground and obviously, twenty five metre ground falls tend to be fatal. Thankfully, there were some things under my control to avoid this scenario and I set about controlling them.

First, as I played back my video of Steve’s fall, I could see that the top cam had ripped, causing Steve to drop onto the next one which was on a longer quickdraw. On my next visit, the route was kind of wet and so I focused on sorting out the gear. The slot looked like a bomber placement. Had it just ripped because of the sheer length of the fall? Probably. But I noted that the slot had a film of soft dusty lichen in the back. With a good brush it had a bit more friction. A slightly different cam fitted a little better and I could squeeze a C3 into the same placement. A slight improvement perhaps?

Above on the headwall, I’d noticed a little slot. Surely that would take a nut? I had mentioned it to Neil and Steve but they did not seem impressed with the placement and didn’t want to bother with it. I found that a BD nut seemed pretty bomber, the only issue was that the ‘crystally’ rock around it could break. But there was also a good skyhook right beside it. Perhaps both of these on a screamer each could actually hold? I think it’s plausible. Even if not, they might prevent the belayer being pulled up so far and give you that crucial extra metre or so if you did take the full ride. Even if none of those things were true, it looked good to have something clipped to the rope. I would almost certainly feel less lonely up on that headwall. This all came with a major downside in that stopping to place these two runners mid crux adds nearly a grade to the physical difficulty of the route. That headwall is very much a power endurance sprint. Adding another 20 or 30 seconds of hanging off a thin sidepull, gradually barndooring off poor footholds while faffing with skyhooks was not ideal. I resolved to pre-clip them to the lead rope and velcro them to my harness to avoid having to do any clipping. At least I could make it a 10 second penalty rather than 20.

Taking a key sloper with my left hand. Neil and Steve used this with the right.

My biggest weapon by far is the ability to work out a good sequence. I made countless changes to it over two days in early October, ending up using some holds with the opposite hand to Neil and Steve, as well as a couple of holds they don’t use at all. One of these allowed me to shake my left arm before taking the crucial crimp in the groove where Steve fell. With this sequence, I linked the climb completely on the shunt six times across two sessions and knew the route was possible. A summer of various mishaps in 2021 had left me a bad case of tennis elbow and this was really limiting me. I couldn’t try the route for long before it hurt too much, and I was not in anywhere near good enough shape to lead it. October was pretty wet anyway and most of the time I’d tried it there were wet holds.

I was working on the assumption I’d just get it all as sussed as possible before winter and then come back the following spring. Task number one was to recover from the tennis elbow to even begin training again. The elbow recovered steadily and I could tentatively start on my 45 board in early November. Even just a few sessions on the board gave me some confidence and in late November I optimistically went down with Iain Small to lead Lexicon. Sadly, the overnight rain had been heavier than expected and it was seepy. At least it drew a definite line under proceedings for the autumn and I could move on.

I planned my winter training as such; December - board. January - boulder projects outside, February and March - endurance training on the board. Training plans rarely survive real life intact, but this one seemed to roughly hold up and as March progressed I had many boulders between 8A and 8B+ under my belt, plus a reasonable amount of endurance work, for me at least. There were niggles; a tweaked finger joint and my usual ankle issues that suddenly seemed to flare. Could I even walk in?!

On the stellar late March forecast I went to find out. I was indeed a bit hobbly but could get to the crag. It was lovely and dry but the wind was raging and I could not warm up. Yet I could link it with my big belay jacket on and numb, glassy fingers. A good sign. I just needed that one confirmatory session in more reasonable conditions. After a rest day, I got it and linked the moves repeatedly, placing all the gear and trailing a lead rope, sussing out exactly how to extend all the runners. Game on. Chris messaged, keen to take pictures if I was trying it. I said it was ready to go and so Natalie and Chris joined me in Ambleside a couple of days later.

On our day on the hill, that keen March wind had died completely and I now was back to the opposite problem of ‘too warm’. Your fingers have to bite those rhyolite crystals. If it is too warm, my skin just rolls off them. This did not fit within my ‘thorough protocol’. How would I feel if I greased off the last move and dropped the length of the crag, for the sake of waiting for a breezy day? And yet, the fact I’ve arranged a climbing partner does weigh on me. I felt bad enough dragging Iain up there and felt silly as we sat about in 4 degrees looking at a dripping crag. If I could just get a half hour of wind, I could see it off. I also had a hunch that I was in good enough shape to just scrap my way up it even in less than perfect conditions. Why not just finish it?

Unfinished climbs have always been a source of chronic pain to me, an ache I can tolerate for long periods when there is no other option. But the minute I can change the picture, I’ll do anything I can to resolve it. When I say ache, I mean that in a good way, like the ache of burning muscles in training. It’s good pain! The minute I resolve it, I’m almost instantly looking to cause it again and have lived this way for 25 years. There is an expression that pain is the cost of being alive and as far as I’m concerned, it’ll stop when I’m dead.

Little bits of breeze came and went and so I continued with preparations. Final bits of velcro were attached to screamers, the rack was laid out on the grass and then attached to my harness in order and we abseiled down. At the absolute minimum, I wanted to force myself to climb to the nut and skyhook on the headwall, no matter the conditions. I could have the opportunity for a confidence building fall from the sloper where Neil did his super high step. If I got to the skyhook and nut, I could test exactly how efficiently I could get them in on the lead. It’s always more of a faff than you would like. If the breeze suddenly picked up and I could hang that wee side pull long enough to get the hook in, maybe I could just commit? Delaying this decision right to the last moment is a classic psychological tactic. It nearly always works, as long as you have the experience to be able to deal with hitting the ‘go’ button when the moment comes.

Committing to the runout on Lexicon. Photo: Chris Prescott

I worked my way up the E6 lower wall and arranged the gear at an awkward kneebar. I hate the delay of lingering on rests on trad routes. Where the rest is purely about putting off the inevitable, I tend to just rally and want to force the outcome. I committed by vocalising a little announcement to Natalie; ‘climbing’ and pulled up on the little undercut. As I took the hold after the sloper, a little sidepull right in front of your face, I clocked the sweat on my fingertips. ‘Don’t go any higher’. The nut went in okay, but I was barn-dooring badly while trying to detach the skyhook from fresh velcro. ‘Get it in and then just grab it’. With the runners in, I relieved the left hand and chalked up, noting that to my surprise the left arm was not pumped. A distracted thought flashed across my mind ‘training fucking works!, that’s cool!’ Back in the present, my feet were somehow already built up level with the skyhook and I was leaving it behind. ‘What are you doing? Don’t go any higher. Grab that skyhook’. ‘Oh fuck sake Dave as if you were ever going to grab the bloody runner. Forget that. Feel that breeze. You’re here, you’ve got a partner to belay and you’ve linked it ten times. Just climb another ten moves and don’t let go of that slot at the end’.

Leaving behind the skyhook and deciding to commit.

By the time that little conversation was over I had the crimp in the groove and was carefully stuffing the back three fingers into the shallow pocket where Steve fell. ‘Oh yes, this spot feels just as high and lonely as I thought it would. Might as well enjoy the mad position, it’s too late for doing anything else. Regardless of the outcome, you’re only going to be here for a second or two’. Setting up for the lunge to the slot, I felt all in the wrong place, my feet were numb and body too tense. I felt like all my weight was on the tiny crimps and was pulling like hell on them. But I also felt I had a lot of power on them. Time to use it! It wasn’t pretty, but I grabbed the slot with a deep grunt. ‘Massive neural drive’ as my muscle physiology lecturer used to say. It worked, with the consequence of a bit of shakiness as the neural drive spilled over on the easier last couple of moves. The security of the huge spiky jug at the top was so comforting, an unquestionable finish line from which you can finally let go of the ache.

I have not climbed all the hard trad routes in England or Wales by any means, but I have climbed quite a few and Lexicon is harder than any of them. Neil’s effort climbing the first ascent is exceptional in my opinion. There are plenty of climbers who could do the moves on it, but I suspect the number who would actually lead it is rather small, at the moment at least. At 43 I’m delighted to be the youngest person to climb it by some margin. Watching both Neil and Steve destroy such a hard piece of trad climbing is a great example that I would like to emulate as my climbing progresses. Age is a funny thing, it can work in multiple ways. The battle scars that come with it can weigh on you, if you don’t just decide to work around them. On the other hand, it can give you an appreciation that if you don’t go and get on the route and get yourself in finishing shape, the time will pass and you’ll never do it. That mindset can put you in a powerful position.

Taking the wee pocket where Steve fell from. Photo: Chris Prescott